Community Cookbook - Reflections on the CLIMAS E&S Fellowship

Introduction

For the last twelve months, I have been on a rollercoaster of emotions; but, as my friends tell me, I am pretty much always on that rollercoaster of emotions, pandemic or not. So, as we near the one-year marker of social distancing in the U.S., I am reflecting on my turbulent feelings and experiences. I spent the majority of the pandemic 3,000 miles away from my family, oscillating between missing them, being scared for them living so close to New York City, and grateful I wasn’t cooped up alongside everyone in our small New Jersey apartment. In Tucson, I was able to keep working, keep getting paid, keep spending time outside, and keep my basic needs met. This came with a lot of guilt as I heard from friends and acquaintances all the struggles they faced with unemployment, food insecurity, immigration, being an essential worker, getting sick with COVID-19, and more.

I think I am still sitting in that guilt, but I also know I have a responsibility to fighting the systems that cause and exacerbate the hardships we are facing. Capitalism, white supremacy, and colonialism undercut almost every choice we make, and we have to be vigilantly anti-racist, anti-capitalist, decolonial, etc. if we ever hope to see a brighter future. This year I learned and engaged with organizing and direct action in a significant way for the first time since undergrad. I was a part of powerful gatherings for Black lives, rallied against police brutality, saw local progressive candidates for office I helped campaign for win their elections, redistributed some of my wealth via mutual aid, and tried to give myself emotional space to process instead of running away from my thoughts. I know it was not enough and that I could always do more, but I think it is important to recognize the small triumphs in the fight for liberation.

In this spirit, food has grounded me. Even though my grand and luscious raised garden bed dreams never came to fruition (not for lack of trying…), I took solace and rejuvenation in the form of cooking, sharing photos of meals in WhatsApp chats, calling distant family members for recipes, and using the kitchen as a space to slow down and intentionally reflect on the world. With all of this in mind, I present a summary of my work with the CLIMAS fellowship program.

Background

While the pandemic not only caused new problems, but exacerbated old ones, the last year also highlighted that in times of peril, scarcity, and harm, people often turn to the land. I noticed people sharing recipes on social media, trying to learn how to make sourdough bread, supporting their neighbors who could not afford groceries, and even starting container gardens.

My CLIMAS project was to develop a community cookbook with Mission Garden, highlighting how food, culture, and sense of place contribute to community resilience, especially in response to pollution, climate change, and injustice. I worked with co-created citizen science project, Project Harvest (PH) and Mission Garden to explore these concepts and start to create the cookbook. My big, queer, earth-centered, and South Asian families teach me that it is important to celebrate joy, which we usually do via food. With this cookbook, I aimed to celebrate how frontline and marginalized communities use food as a defense against harm and as a seed for resilience.

PH participants have also been asking for more deliverables and this cookbook is a welcome material. In addition, the Mission Garden has wanted to expand and develop their culinary offerings. To create the cookbook, I am gathering recipes shared by PH participants and Mission Garden community members then clarifying, recipe testing, photographing, and stylizing them.

Stakeholders

PH is a co-created citizen science environmental monitoring study assessing contaminants in harvested rainwater, garden soils, and garden plants in four Arizonan communities: Tucson, Dewey-Humboldt, Globe/Miami, and Hayden/Winkelman. PH also focuses on participant learning, individual/community action, and systems change. There are over 150 participants who collect samples from their homes and send them to the University of Arizona for analyses. Samples are assessed for inorganic, organic, and microbial contaminants with resulting data shared to participants in a variety of ways (website, personalized booklets, phone calls, art installations, written reports, data-sharing events, and more). Participants primarily use their harvested rainwater for irrigating home gardens and want to know how safe their soil, water, and plants are for various uses, including consumption.

Figure 1. Photograph of Project Harvest promotoras and principal investigators passing out sampling materials.

Mission Garden is a four-acre garden at the base of Tumamoc Hill in Tucson, AZ. The goal of Mission Garden is to honor the over 4,000 years of agriculture in southern Arizona through gardens representing the many cultures and traditions that have called this area home. There are Hohokam, Yoeme and Yaqui, Tohono O’odham, Akimel O’odham, Mexican, Chinese, and Spanish gardens with more on the way representing African and Black culture and history in the Tucson area.

Figure 2. Photo of several plots at Mission Garden with A mountain in the background.

Outputs

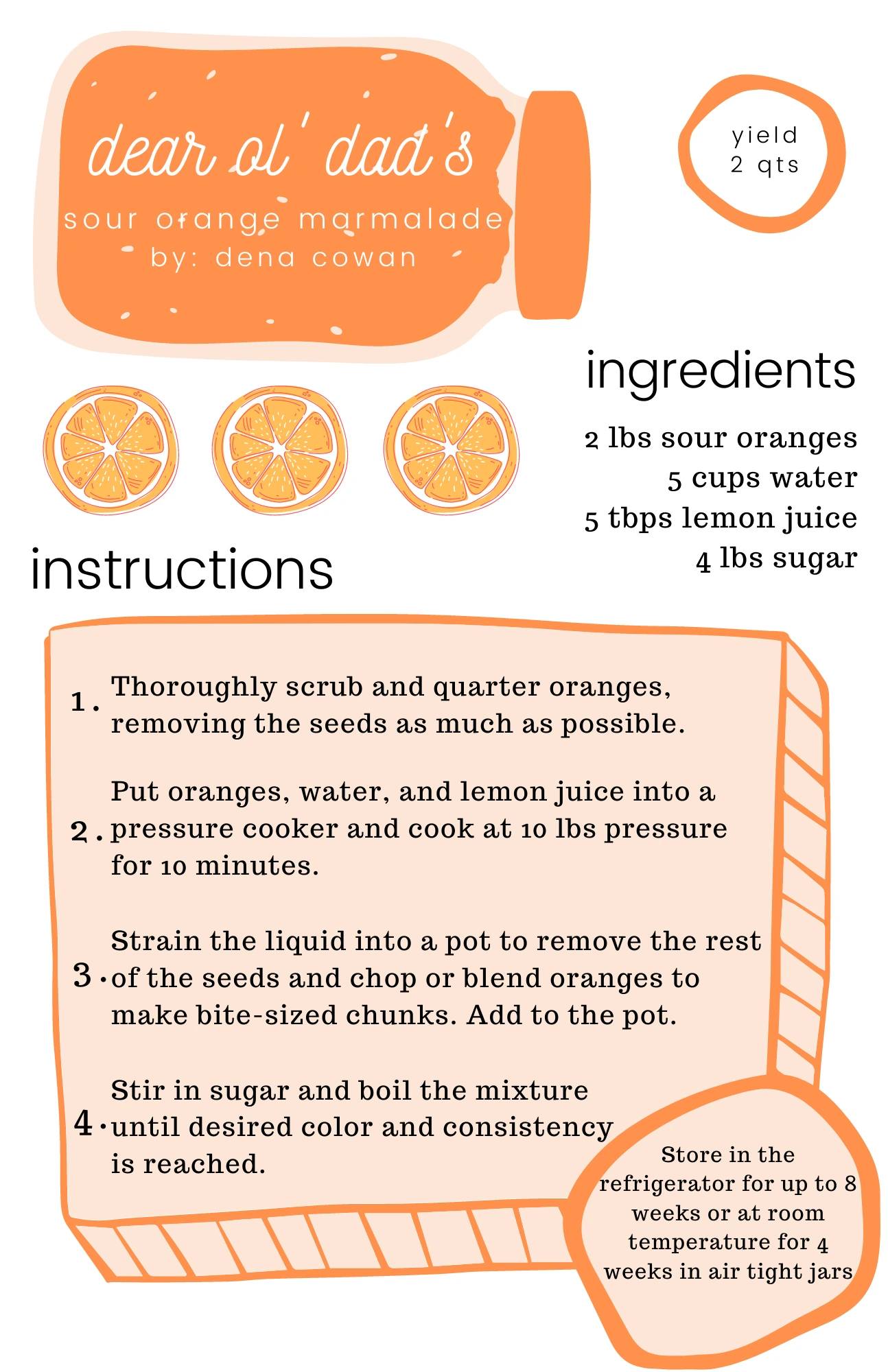

While research plans changed drastically over the course of the last year, I was excited to start the cookbook and put together several recipes to give a taste of what the book will look like. Here are a three:

Figure 3. Dear ol’ Dad’s Sour Orange Marmalade recipe.

Figure 4. Fire cider recipe with Desi and Thai variations.

Figure 5. Tepary bean hummus recipe.

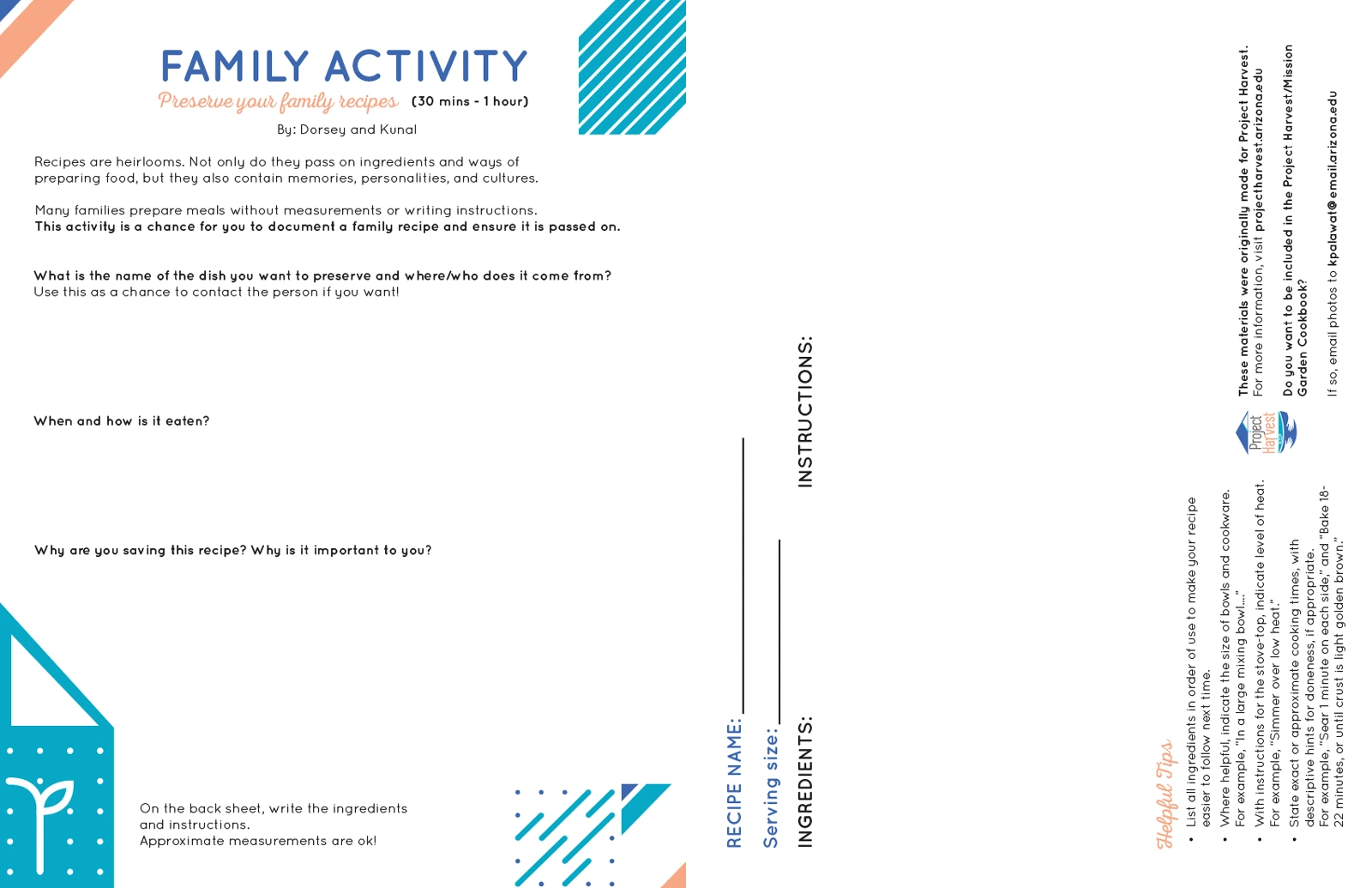

I also worked with researcher and artist, Dorsey Kaufmann, to create an activity based around documenting family recipes. As the worksheet indicates, “Recipes are heirlooms. Not only do they pass on ingredients and ways of preparing foods, but they also contain memories, personalities, and cultures.” When I recently visited home for the first time in a year, through this activity, I was able to spend time with my family talking about a dish that we had never written down before, Pav Bhaji. It is a delicious Desi meal with tomatoes, potatoes, and a specific spice blend, usually eaten with bread. We wrote our recipe down and had a great time talking about all the ways various Aunties and Grandmas in our family make the dish their own.

Figure 6. Family recipe activity created by Dorsey Kaufmann and Kunal Palawat.

Next steps

Future work with this cookbook experience is to finish gathering and adapting seven more recipes, creating three YouTube cooking videos, finalizing three Spotify playlists to listen to while cooking, and designing the rest of the cookbook. I also hope to include gardening tips for the Southwest US and community reflections on COVID-19.

As I reconnect with Mission Garden, I will accomplish what I set out to do last year and help expand Mission Garden’s culinary offerings by hosting cooking classes. If those are well received, I will also offer online cooking classes for PH community members. During these classes, I will facilitate space to dialogue about food, pollution, and ecosystem/human health.

Figure 7. The Ramírez-Andreotta lab collecting soil samples at Mission Garden circa 2015.

Lastly, as summer 2021 comes to a close, I hope to continue environmental monitoring of Mission Garden that started in 2015 with a focus on understanding the human health risks and benefits associated with the plants, soils, and waters in the area.

2020 Reflections

This year, amidst the struggle for Black lives and a more just society, COVID-19 pandemic, and personal hardship, I found myself wildly ill-equipped to fully engage and commit to research. For the majority of the year, I felt lost, insecure, and isolated. I felt like I was failing at every turn and my mental health suffered even more than normal. I started the fall 2019 semester going to Mission Garden every Thursday morning to work, pick beans, weed garden beds, and talk with other volunteers and visitors. But at the beginning of the pandemic, I stopped going to the gardens and all but paused work on the cookbook and other projects to focus on my health and community organizing. I aim to restart relationship building once COVID-19 vaccines have been well distributed around Pima county and finish out the cookbook by the end of summer 2021.

I learned a lot about the importance and need for rest; while, at the same time I feel like I never actually stopped working, organizing, or doing. I have also learned a lot about flexibility, growth, and the need to listen to calls for change. Especially in community-based and co-created science, researchers must be dynamic in their approach and respond to the needs of their community and themselves. Some of those responses have looked like quickly transitioning to Zoom in lieu of in-person meetings, wearing masks, pausing field work, having virtual cooking classes, changing research questions, or sending money to people in need through mutual aid. But there is always more that could have and should have been done. I hope we all take time to reflect on 2020 and the systems of oppression and liberation that came to the public surface so that we may make informed and decisive change for a better future.

In the vein of use-inspired, community-based, and democratized science, this CLIMAS fellowship gave a dedicated space for fellows to regroup and consider the role of the pandemic and social unrest in research. In no other research setting, was I ever asked how COVID-19 impacted me and my capacity to live. In most other meetings, we did not spend a substantial amount of time sharing about power and privilege and their impacts on our communities, stakeholders, research, and more. Is research important if it does not respond to the needs of the most marginalized/impacted? What is the point of work that is disconnected from the public, ignorant of the political arena, and/or miscommunicated to relevant stakeholders? How do we cherish the humanity and needs of researchers, co-researchers, community members, and the Earth all at once?

For any future work I do, I will ask myself these questions and if my responses are not substantial enough, then the study should not happen unless it changes to be more liberatory. I urge everyone reading this article to similarly create a set of guiding questions to ground your research so that it can have a meaningful impact and limit how much harm the work perpetuates.