Navigating Floods and Fieldwork in Honduras

Ulúa River, El Progreso, Honduras – a river that frequently floods surrounding areas during heavy storms.

Fieldwork, like the natural phenomena we study, rarely follows the path we anticipate. My fellowship journey in my research studying flood vulnerability was designed to bridge technical satellite data with community narratives – creating a more comprehensive picture that spans from pixels to people. What I couldn’t foresee was how this experience would evolve into a lesson in adaptation itself. As political circumstances shifted with the change of administrations in the US and long-established agencies dissolved overnight, I found myself not just studying resilience in communities affected by floods, but also embodying it within my own research path. Fieldwork so far has become more than an academic pursuit; it has transformed into a lesson of flexibility and finding momentum again after unexpected events hiccup collaborative plans.

When I originally started my research project, I imagined I would study floods in Honduras through a relatively clear approach: how floods disrupt people’s lives, especially for those already facing other challenges. To study this phenomena, I essentially asked: how do floods produce and reproduce vulnerability in Honduras? With satellite data on one hand and community engagements on the other, I planned to bridge the gap between pixels and people, between quantitative data and lived experiences. My goal was to help create useful flood data that local practitioners could use for future flood impacts while also contributing to vulnerability literature more broadly.

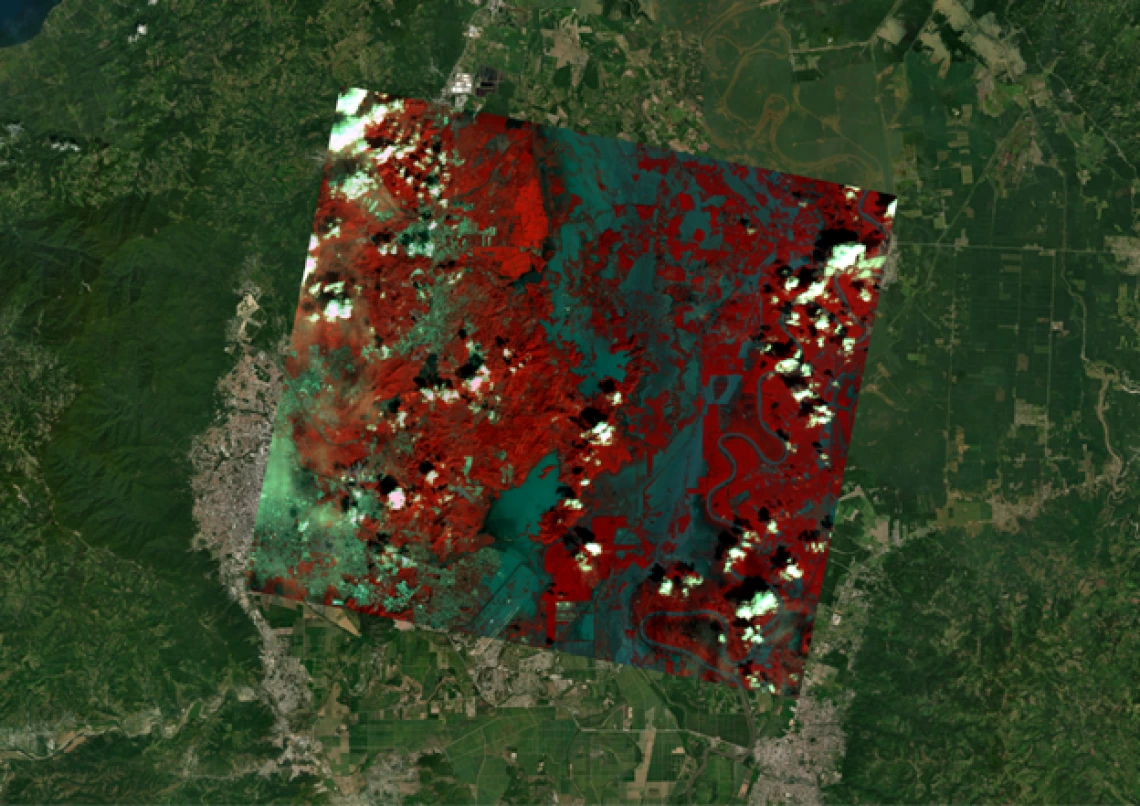

A false-color satellite image showing the extent of flood waters post-flood event, Cortés/Yoro, Honduras.

Community engagement and speaking with local residents about their experiences with floods is a central component to my research. These narratives provide meaning to the otherwise impersonal data collected by satellites. The satellites pass overhead, silently witnessing the land, their sensors merely collecting light reflected from the Earth’s surface. Each pixel captures the physical scene but misses the human dimension. What satellite imagery shows only as objective pixels on a screen, conversations with community residents reveal how these flood events actually impact livelihoods on the ground – insights that remain invisible from space alone.

But much like the variable nature of the floods that I study, research plans – especially those that are collaborative in nature – rarely go as planned.

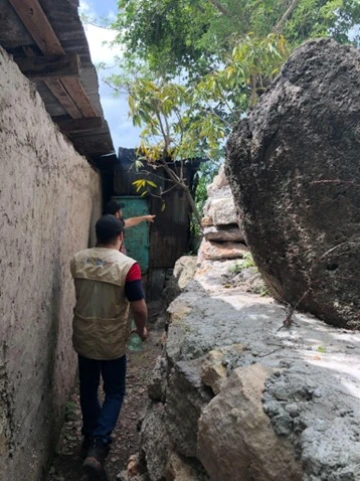

Speaking with a resident in a flood-vulnerable neighborhood about her experiences and recovery since Hurricanes Eta and Iota of 2020, San Pedro Sula, Honduras.

The importance of local partnerships

Prior to this project, I knew that building relationships with partners was essential for collaborative work and understood that this took time and patience. This became further emphasized over the course of my project: collaborative research is profoundly time-consuming. My project relied on partnerships with local stakeholders – particularly one NGO, GOAL, who has deep ties to communities in northern Honduras where I study. I spent two years building and maintaining a relationship with folks working at GOAL. These relationships flourished most naturally in person, where any barriers felt less imposing and we could navigate conversations more fluidly face-to-face.

Being on the ground and speaking with community partners is where the heart of this research lies and is felt most. GOAL’s office in San Pedro Sula is where I spent a lot of time with project managers and other staff discussing their ongoing work, my proposed work, and identifying overlapping interests. My original visit with GOAL in the summer of 2023 sparked numerous collaborative possibilities. We imagined how we could co-host workshops and how we could design useful flood data approaches together. Most critically for my dissertation work, we identified neighborhoods where I could interview residents through GOAL’s established community connections – a critical factor for conducting fieldwork in the barrios of San Pedro Sula and surrounding areas. These ideas were ways in which my research skills could complement their USAID-funded Barrios Resilientes project, a partnership whose stability I never once questioned as I prepared for my year-long stay.

Visits with local residents in flood-vulnerable neighborhoods, San Pedro Sula (left) and Villanueva (right), Honduras.

When plans wash away

Just as populations across the globe have learned to adapt when floodwaters surge through their communities, researchers must also adapt when circumstances suddenly shift. Within weeks of arriving for my year-long stay in Honduras, the political landscape in the US transformed dramatically. The dismantling of USAID operations was devastating – not just to my research plans in Honduras, but to the entire ecosystem of support for vulnerable communities across the globe.

With USAID as their primary funding source, GOAL had no other option but to close their local office in San Pedro Sula. The very office that served as my home base during my previous visit and the center of my collaborative network, gone. The partners who knew my project, who were going to assist me in the field, were no longer available. The workshops I had envisioned, the fieldwork I had planned, the collaborative components we aspired to complete – it all needed to be completely reimagined. Knowing that the office is shut down, and knowing that some of the employees left the city entirely as a result, I felt the full weight of this reality. This moment provided a sobering reminder that collaborative research is subject to forces far beyond our control. Even with years of planning, circumstances can change overnight, leaving researchers to navigate challenging situations.

Watermarks and damage left behind by Hurricanes Eta and Iota on the interior walls of the home of a local resident, San Pedro Sula, Honduras.

Finding new channels

My time in the field these past two months has shifted focus from completing a flood database to building a new foundation that can sustain this research in the long term. Rebuilding my network in Honduras has been another slow, time-intensive process. Finding local partners who share similar interests and have the capacity or resources to welcome an outside researcher has proven challenging. More crucially, I’ve found it particularly difficult to find and connect with organizations that maintain strong community relationships in Honduras’ most vulnerable communities – something essential for conducting this fieldwork. Despite these challenges, I am still committed to my vision of creating the flood database and web application for stakeholders to use, but I accept that this timeline may be delayed until further connections are made and I have partners who can help guide this process as priorities and circumstances have now changed. Finding new paths and being flexible in the face of changing circumstances lies at the heart of collaborative work, as projects rarely unfold according to plan. In some ways, this interruption in my experience reflects the very phenomena I’m studying: the way humans adapt to disruptions, leaving them to find new paths forward when established routes become blocked. Just as floods reshape landscapes and change the course of both human and environment processes, unexpected changes have reshaped my research.

Local resident pointing out the height of previous flood waters, Villanueva, Honduras.

Further exploring a new angle

As my research path has meandered, it has naturally developed and discovered new areas to explore, and has been especially heightened lately due to my unexpected changes in plans. The latest aspect I’ve been investigating is how vulnerability is not merely a current condition but can also be the product of long historical processes – particularly colonial and neocolonial interventions in the landscape.

One chapter of my dissertation now focuses specifically on how certain entities fundamentally altered Honduras’s physical landscape, creating legacies of flood vulnerability that persist across generations. Their development projects of rechanneling rivers and implementing other land-use changes to maximize fruit productions reshaped hydrological systems in ways that continue to channel floodwaters and shape floods in the landscape today.

This shift in my research focus has been thought-provoking and has opened up new ways of considering connections in flooding and vulnerability. I’m exploring how to use satellite imagery not just to document current flood patterns but to trace the historical evolution of landscapes shaped by colonial powers. By layering historical development maps from archives with contemporary flood data, I can begin to visualize how past interventions create present vulnerabilities. This perspective extends beyond Honduras, raising questions about how colonial legacies shape vulnerability to environmental hazards across many regions. It challenges us to consider how historical factors continue to shape vulnerability patterns we observe today.

A modified channel of the Chamelecón River that is susceptible to flood hazards and frequently floods surrounding homes during heavy storms, San Pedro Sula, Honduras.

Looking Ahead

As the academic year draws to a close, I find myself with a deeper appreciation for the complexity of human-environment research. The technical challenges of detecting floods using satellite imagery have been matched by the human challenges of navigating changing partnerships and uncertain political times. Behind every data point lies real communities with their own stories of resilience and adaptation.

The flood database will be completed, the workshops will happen, and the knowledge will be shared. It may take longer than I initially hoped, but like the communities I work with, I’m adapting to changing conditions while keeping my ultimate goals in sight. In the end, this fellowship year hasn’t been the straightforward path I imagined, but rather a journey that authentically reflects how collaborative work functions, in complex, unpredictable realities that require the researcher to be adaptable and persistent.