Research on the Little Bighorn River - Reflections on the CLIMAS E&S Fellowship

Project Background

Nestled in the valleys between Iisaxpúatahchee Isawaxaawúua/The Bighorn Mountains and the rolling plains of the Powder River Basin, Apsáalooke people make their home within the Iisaxpúatahcheeaashe/Big Horn River, Iisaxpúatuahcheeaashiakaate/Little Bighorn River (Figure 1), and Alúutaashe/Arrow Creek watersheds. I do not have a first memory of the Little Bighorn River because it is all I have ever known. I was raised along this river that has taken care of my people for many generations. It flows north from the heart of the Big Horn Mountains which begins in Wyoming – traditional Apsáalooke territory – into the crevices of the Cheétiish/Wolf Mountains eventually joining the Big Horn River at the northern end of our reservation. My people have always relied on our water resources and remained connected to the water as an element and buluksée/water creatures. We have been instructed on how to care for the river and use the river for ceremonial practices such as Tobacco Society, Sundance, sweat lodges, and bundle ceremonies. We are told to feed the river when the cotton first falls in the spring, and to ask for protection for our children as we interact more with the river due to the warmer months. The Little Bighorn River has always provided for my people and, for that, we are forever grateful.

Figure 1. Me posing at my second sample location which is downstream from the headwaters of the Little Bighorn River

As a student in the Department of Environmental Sciences at the University of Arizona, I am trying to understand the relationship between seasonal river flows and pollutants – termed the concentration-discharge relationship - by identifying what chemicals are in surface waters samples in the Little Bighorn River at different times of the year. From a hydrology perspective, we know that water resources are a directly correlated to the amount of moisture that was received throughout the differing seasons. In the winter, the river water flow is low and at its calmest because most of the moisture was used throughout the year by many users and the snow has not yet melted in order to recharge the water supply. In the spring, rainfall and milder temperatures melt away the ice and snow transitioning it into liquid form that refills rivers, creeks, and aquifers allowing the river water flows to begin to increase. With the hot blaring sun in June, the river is at its highest flows because the snow and ice recharged the water which also prompts more usage of the water for recreational, domestic, municipal, and agricultural purposes. The river flows gradually decrease as time passes into the fall season where it eventually reaches the hydrologic new year. The river is now back to its original calm flow as the colder months begin to dominate again. I am particularly interested in how pollutants are behaving according to these changing seasonal flows of the river that we witness throughout the year. Not only does this provide essential information from a watershed management perspective but it gives a better sense of what is occurring in the river especially when we think about ceremonial uses of water during specific seasons.

Field Work

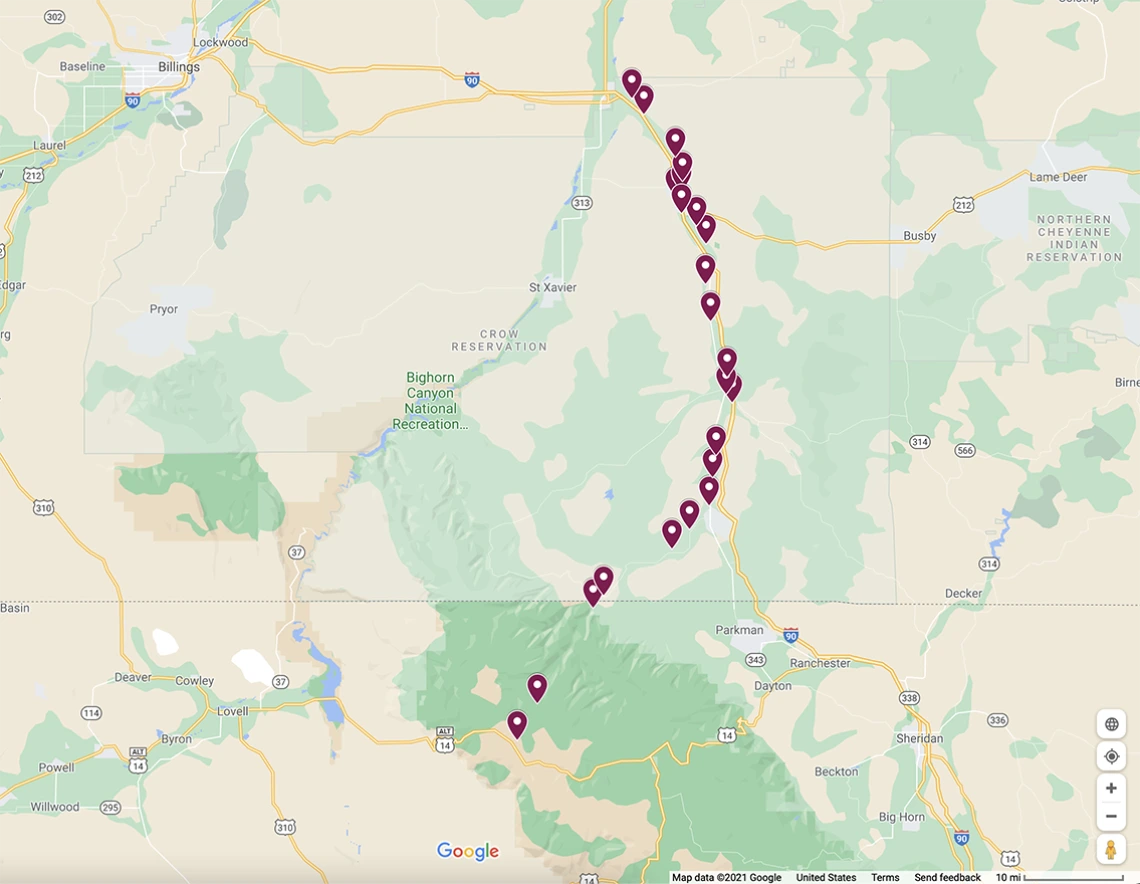

Despite the crazy year we have had, I was fortunate enough to continue my research. I returned home to Montana in June to collect samples during the peak flow season of the water year. Returning home to sample consisted of a busy five-day work week. I take the first day to prepare ensuring that all of my sample bottles and supplies are ready to go. I did last-minute preparations such as fill up the gas tank for the long drive, pack ice into coolers for sample storage, load all supplies into my rental truck, grab snacks for the road, and finalize a playlist to keep myself company. This specific sample trip in June was special to me because - despite living along the Little Bighorn River my entire life - this was the first time I had ever gone to the headwaters. The drive to the headwaters in the Bighorn Mountains is approximately an hour and half drive from where I grew up. I find it pretty amazing to witness the growth of the river as it flows downstream to its ending. I collect water samples at 23 different locations along the longitudinal profile of the river beginning at the headwaters and ending at the confluence of the Little Bighorn River to the Bighorn River (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Map of my sample locations along the profile of the Little Bighorn River which sits on Apsáalooke territory.

I collected in December 2019 at the same locations along the river beginning at the Montana-Wyoming state line (no headwater samples were collected due to snow). The first day is spent making the drive into the Bighorn Mountains to collect two samples near and downstream the headwaters (Figure 3). While collecting at the headwaters, I was visited by a cow (female) elk and young moose, trekked through snow and glacial till, and sampled in the coldest water I encountered along the entire stretch of the river. My feet to my mid-calves were bright red from standing in in the frigid water in middle of the Little Bighorn River. The river slowly flows through rocks and boulders making its way down the mountain. The width of the river at this point is so small that I can place my left foot on one side of the bank and my right foot on other side. Whereas, the river width near the end is so wide, I have to walk approximately 20 feet to reach the middle of the river and the height of the water is almost to my waste. The following three days consist of collecting samples at seven locations each day along the longitudinal profile of the river. After each day, I travel to Billings, Montana – which has the closest FedEx location to me and can be at most 113 miles away - to ship the coolers packed with wrapped sample bottles and ice packs back to the Arizona Laboratory for Emerging Contaminants and Chorover Lab.

Figure 3. Collecting a sample near the headwaters of the Little Bighorn River.

Every sample location was picked strategically based on proximity to contamination hotspots, tribal concerns, and tributary locations. I collect four sample bottles at each location which tests for inorganic and organic elements as well as use a device to measure pH, water temperature, and dissolved oxygen (Figure 4). Another cool aspect of my sampling trip in June was the fact I had a drone to document my sampling journey and provide an amazing bird’s eye view of the Apsáalooke land that I am privileged to come from. My uncle, Zane of Aurora Hiraeth Visuals, edited and produced a short documentary about my research journey that was filmed by both my partner, Talon, and my uncle. In this video, you catch a glimpse of my research purpose and endeavors as well as Apsáalooke homelands all along the Little Bighorn River. The joys of doing research at home means that my sample trips are a family affair and I revisit familiar places. I sampled near my favorite swimming hole where I was raised, in Medicine Tail Coulee where the Battle of Little Bighorn took place, and near the fasting place of Chief Two Leggins. I enjoyed hearing stories of moving cattle on horses from my grandfather, laughing with my nephew and nieces while cooling off in the river, and absorbing the power that this river perpetually gives.

Figure 4. Measuring pH, dissolved oxygen, and temperature in Medicine Tail Coulee.

2020 Reflections

I write this reflection with a broken heart. This year has challenged me in more ways than I would have liked or even expected. I am overjoyed by the fact that I was able to continue research, but it was also done with a broken heart. COVID-19 continues to extremely impact my people in unimaginable ways that we were not prepared for. My people have lost knowledge-holders, language speakers, aunties, uncles, mothers, fathers, grandmothers, and grandfathers. One hard lesson that I have learned is that my heart hurts every single time I see a young person post about the person just lost and how much that person means to them. We speak about how we always go to our loved ones for guidance whether that be personal, daily, cultural, or spiritual. It has been so heartbreaking to witness and feel so much loss within our community. Although, we have the fifth largest reservation in the United States, we have a small tight-knit community compared to most tribal reservations/communities. Grief and loss almost feel like a ripple effect because we all have all felt or know someone who has dealt with heartbreak, and we are continuing to do our best, to not only stay healthy and practice CDC guidelines, but moving forward while mending our hearts.

To be truthfully honest, I am in this constant state of trying to balance panic, grief, and hope. I find myself in an interesting space of aligning priorities, doing my absolute best to receive an education with a broken heart, and painfully accepting the fact that many of those we turned to are now making their way to the otherside camp. With so much loss, it has brought me to question myself and the work that I do. I think it is very real to question the validity of the work that you are doing, and I found myself at this interesting point. I have so many questions for myself and have strategically thought about how I am going to move forward in all aspects of my life. I am so grateful that the CLIMAS fellowship has provided a space for me to intentionally confront my thoughts and feelings regarding the intersection of life and academia/research. I am thankful that my cohort and mentos reminded me that it is okay to feel confused and out of balance. They reminded me that it is okay to forgive myself in whatever way that I can. They reminded me that the work that I do is absolutely important and essential to my community. They provided light in times of darkness. I am so thankful for their support and guidance throughout this fellowship experience and for always providing a safe, comfortable space.

This past year was especially difficult for me and I am still having a hard time. My great-grandfather (mother’s maternal side), great-grandmother (mother’s paternal side), clan mother who named me, grandfather who gave me certain rights, and dear friends made their way to the otherside camp this past year and all have played a major role in the person I am today. There is really nothing that prepares you for the days you lose your kaales/grandmas and kaakes/grandpas. I had this naïve assumption and crazy imagination that my kaales and kaakes would live with us forever. It was hard to imagine living a life without them, but I also knew that they did everything they could to ensure that we had the tools and knowledge to navigate this life. I am very fortunate to have had my great-grandparents this far in my life and to know that they live full and wonderful lives. Often times, we think we are so far removed from history but in reality, my people still have deep connections to our ancestors who thrived in the Buffalo days. I was raised by people who were raised by those who prospered in the Buffalo days and survived attempted genocide. I am proud to say I come from strong, caring, and resilient people. While in mourning, I find myself balancing heartache and aspirations. I know that my great-grandparents have prayed for me to be where I am in life and I will do my best to honor their wishes by continuing to work hard in obtaining my education.