Notes From the Field: Thinking Outside the Box with Great Basin Natural Resource Managers

On June 25-27, 2014, a team of researchers from CLIMAS and the California-Nevada Applications Program (CNAP) convened a workshop at the Desert Research Institute in Reno, NV. The goal? We wanted to address the complex and uncertain future of Great Basin land management in the Central Great Basin (California and Nevada), and to provide state and federal agency partners with streamlined and purposeful means of incorporating climate change information into land management practice.

On June 25-27, 2014, a team of researchers from CLIMAS and the California-Nevada Applications Program (CNAP) convened a workshop at the Desert Research Institute in Reno, NV. The goal? We wanted to address the complex and uncertain future of Great Basin land management in the Central Great Basin (California and Nevada), and to provide state and federal agency partners with streamlined and purposeful means of incorporating climate change information into land management practice.

In addition to myself, the project team includes:

- Tamara Wall (CNAP and Desert Research Institute)—a social scientist with a knack for methods and metrics assessing how climate knowledge is communicated, used and applied to environmental hazards

- Tim Brown (CNAP and Desert Research Institute)—a long-time collaborator with CLIMAS and one of the nation’s leading fire climatologists

- Holly Hartmann—whose ongoing work on scenario planning and decision support is pivotal for land management agencies such as the National Park Service and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and

- Julie Brugger (CLIMAS)—an anthropologist whose work on climate concerns among rural stakeholders and land managers brings in consideration of the social and cultural factors that influence the use of climate information in decision making.

Background

The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) manages the vast majority of public land in the Great Basin, and they are interested in practical methods for incorporating climate change information into their on-the-ground practices and operational strategies for land management.

The first phase of our project was funded by the BLM, which is interested in using results from its Rapid Ecoregional Assessments (REA) program in climate adaptation planning, and we put together a workshop to introduce two scenario-planning methods:

- Adaptation for Conservation Targets, or ACT, and

- Strategic Scenario Planning, or SSP.

We wanted to assess the best uses of these methods, and to learn from workshop participants the best ways to combine these methods for effective planning and implementation of adaptation strategies. Attendees of previous workshops gave feedback that zeroed in on two key ways these methods could be used: some were seen as useful for quick and practical action—a key concern for field managers—while others were seen as more useful in thinking holistically about landscape scale ecosystems—which can assist in long term planning. This split perspective is important and continues to inform our plans to better incorporate REA information into adaptation planning.

Cheatgrass

Our advisory committee suggested that we focus on the sagebrush-steppe ecosystem, and turn to the challenge of managing cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum). Cheatgrass is an invasive species that is viewed as an environmental game changer in the Great Basin, to the point that BLM researcher Mike Pellant calls it “the invader that won the West.

The characteristic red/purple hue of mature cheatgrass is visible across the Great Basin - NV 306 near Beowawe, Nevada - Photo: Wikipedia Commons

The characteristic red/purple hue of mature cheatgrass is visible across the Great Basin - NV 306 near Beowawe, Nevada - Photo: Wikipedia Commons

Why is cheatgrass such a threat and what does climate change have to do it? Cheatgrass is drought-tolerant, is a prolific seed producer, and it is successful at outcompeting native vegetation for resources (water). Not only that, but it thrives in disturbed areas, especially post-fire, but it typically goes dormant and dries out sooner than native plants, meaning it’s presence actually increases the risk of fire. This means that in the Great Basin, a post-fire landscape can quickly become dominated by cheatgrass, which provides a blanket of dry fuel lying in wait for the next fire. Once established, it is incredibly difficult to break this cycle. This threatens the entire sagebrush-steppe ecosystem, beginning with Big Sagebrush (Artemesia tridentata)—the centerpiece of the ecosystem’s web of interactions and ecological dependencies—and ending with all the species dependent on the native sagebrush environment ranging from big game species, such as elk and deer, to regionally important species such as Sage-Grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus) not to mention a whole network of related animals including mammals, reptiles, insects, and birds.

Why is cheatgrass such a threat and what does climate change have to do it? Cheatgrass is drought-tolerant, is a prolific seed producer, and it is successful at outcompeting native vegetation for resources (water). Not only that, but it thrives in disturbed areas, especially post-fire, but it typically goes dormant and dries out sooner than native plants, meaning it’s presence actually increases the risk of fire. This means that in the Great Basin, a post-fire landscape can quickly become dominated by cheatgrass, which provides a blanket of dry fuel lying in wait for the next fire. Once established, it is incredibly difficult to break this cycle. This threatens the entire sagebrush-steppe ecosystem, beginning with Big Sagebrush (Artemesia tridentata)—the centerpiece of the ecosystem’s web of interactions and ecological dependencies—and ending with all the species dependent on the native sagebrush environment ranging from big game species, such as elk and deer, to regionally important species such as Sage-Grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus) not to mention a whole network of related animals including mammals, reptiles, insects, and birds.

Workshop

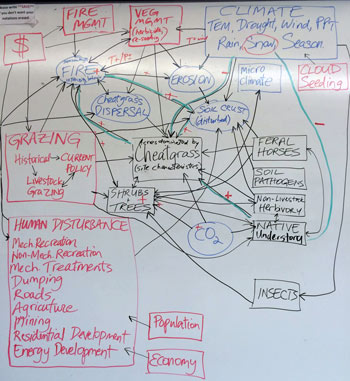

In preparation for the workshop, the advisory committee and the research team developed a conceptual map of the relationships and interactions between cheatgrass and other factors, such as soil moisture, native vegetation, fire, erosion, grazing practices, energy development, road building and, of course, observed climate variation and projected climate change.

On the first day of the workshop, we used this map to explore the direct and indirect linkages between climate and cheatgrass, and identified points in the system where management could implement strategies in the next decade, to affect the spread of cheatgrass over the next 50 years. This method of addressing future changes is called Adaptation for Conservation Targets, or “ACT” (Cross et al. 2013), and it is used by conservation groups and their partners to quickly develop on-the-ground climate adaptation actions. Through ACT, we focused on aspects of environmental management that managers can actually control. This is not unlike riding on roller skates through an obstacle course. You adapt to the obstacles, but you remain connected to the ground.

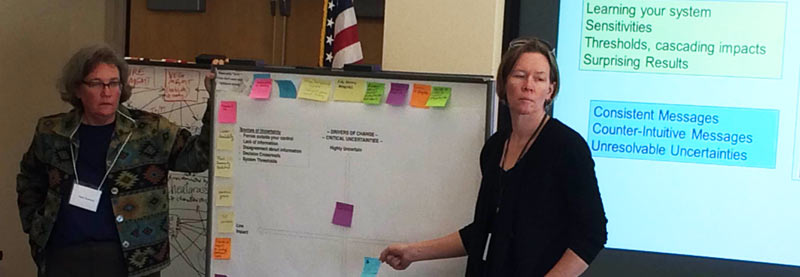

Holly Hartmann and Tamara Wall Listening to Feedback from Participants. Photo: Gregg Garfin

Holly Hartmann and Tamara Wall Listening to Feedback from Participants. Photo: Gregg Garfin

On the second day of the workshop, Holly Hartmann introduced Strategic Scenario Planning, or “SSP” (Weeks et al. 2011), which is a method that focuses on factors outside of resource managers’ control, such as regional population growth, laws, the economy, public policy, and climate variability and change. Holly used SSP to help workshop participants develop new ways of thinking about an uncertain future, and for dealing with combinations of highly variable factors—such as changes in winter precipitation, which are critical for cheatgrass growth, and future funding resources, which are critical for implementing projects. The SSP method helps people expand thinking beyond day-to-day actions, to consider how factors may change and interact over time. This is more akin to learning to surf, you are developing your skill and balance – your ability to adapt and respond to unknown changes, but the ‘ground’ beneath you is constantly shifting and unpredictable.

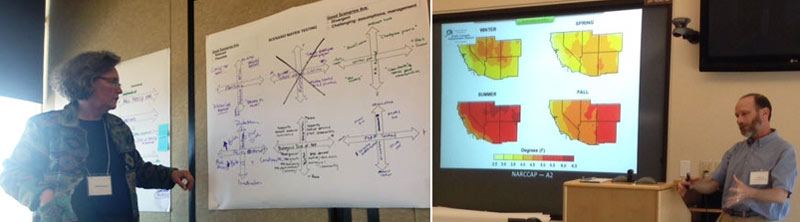

Holly Hartmann discusses SSP method - Gregg Garfin on Overview of Climate Patterns

Holly Hartmann discusses SSP method - Gregg Garfin on Overview of Climate Patterns

By the third day of the workshop, the participants—a great group of highly motivated and dedicated land management professionals from Great Basin state, tribal, and federal agencies—were skating and surfing along. They provided us with great feedback about using our two adaptation planning methods, and the contrast between the two approaches facilitated a lively and engaging discussion that forced people to consider various overlapping perspectives.

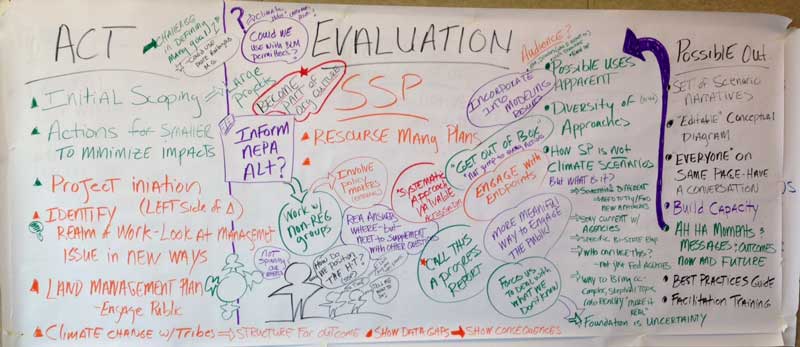

Skating and Surfing Along - The Fruitful Results of Engaged Discussion of ACT/SSP Overlap with Participants - Photo: Gregg Garfin

Skating and Surfing Along - The Fruitful Results of Engaged Discussion of ACT/SSP Overlap with Participants - Photo: Gregg Garfin

Lessons Learned

For the researchers, it was amazing to see how the ACT process—which focuses on linear chains of logic to connect climate, environmental change, management opportunities, and management strategies—enabled the workshop group to apply logic statements to the mind-expanding SSP process. The combination was far more powerful. One workshop participant specifically highlighted the future scenario methods as providing a refreshing contrast to “ready, shoot, aim!” approach that is typical in triage management that simply holds on for dear life dealing with the crisis du jour. Another workshop participant singled out the SSP approach, because it didn’t require everyone to agree on what might happen in the future, but that it encouraged participants to embrace complexity and uncertainty while provoking ideas about how to deal constructively with aspects that are outside of managers’ control.

Our research team is reviewing and refining reports describing the lessons learned at the workshop, but we are also preparing for the next phase of our project (funded by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration - NOAA). Our next step is to organize a working group taken from workshop participants, who are quickly becoming experts in using the REA, to develop a framework for integrating the REA into both ACT and SSP processes. A new national-level dataset on BLM lands offers us the opportunity to inform how the REA data can be used in climate change adaptation planning and management implementation.

Future

We have a webinar planned for October 2014 to build out the scenario sets developed in the June workshop. We plan to hold a second workshop in November to apply the ACT and SSP processes to strategic management planning. This is an ongoing learning process of how to use multiple scenario methods, individually and in concert, and in the near future, we will incorporate the rich array of future climate and ecological projections from the BLM’s REA studies. We are hopeful that many of the attendees from the first workshop will join us in November, and we anticipate an infusion of ideas from new attendees on how we can best start planning for the future in the Great Basin Region.

The project website contains information about the project and the workshop described in this posting.

Gregg Garfin is Deputy Director for Science Translation & Outreach, Institute of the Environment, and Associate Professor and Associate Extension Specialist in the School of Natural Resources and the Environment, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ

Tamara Wall is Assistant Research Professor, Division of Atmospheric Sciences, Desert Research Institute, Reno, NV