Mapping tarps and stories to spotlight inequitable disaster recovery

Amidst the pandemic in 2020, I was living in Corvallis, Oregon, when wildfires lit the sky blaze orange and draped hazy smoke across the state for weeks. A year later, the Pacific Northwest heat dome brought unprecedented temperatures. These two episodes laid bare the impacts of a changing climate. During the fires, homes were destroyed, and people were displaced to nearby hotels and shelters. Hundreds of elderly, houseless individuals, and outdoor workers died from prolonged heat stress during the heat dome.

As time passed, the fires and heat dome faded to the background in state and national news, only to be replaced by the latest disaster. While the news coverage dissipated, the stories and memory of the events lingered with me. I wondered what was still being done for households and individuals without support networks to recover. How many homes were being rebuilt? How many were still living in hotels? How many were without air conditioning? How could answers to these questions be tracked at the individual or building level and be used to inform decision-making about allocating resources or planning for future extreme events?

These thoughts stayed with me on my move to Tucson. During my first week as a Geography PhD student at the University of Arizona in August 2021, another event grabbed headlines, this time hundreds of miles away on the Gulf Coast. Hurricane Ida struck southeastern Louisiana, causing massive electrical outages. My concern about the long-term recovery response to the heat dome and wildfires remained while following accounts of Ida’s aftermath. One article netted my attention. It was a news story about blue tarps being installed on the roofs of damaged homes to protect structures until roofs could be repaired. The blue color of the tarps was striking (e.g., Figure 1).

Figure 1. Blue tarp on a home in North Lake Charles in August 2022. Photo by author.

As a Geographer who uses satellite imagery (images taken from satellites of the Earth’s surface) to understand human-environment interactions, I immediately wondered if the tarps could be seen from space. A quick search of the latest available high spatial resolution imagery confirmed my suspicion that blue tarps were detectable in satellite imagery (Figure 2). Satellite imagery is routinely collected thru time, providing an archive of imagery of the same location. This stream of historical data allows remote sensing scientists to trace changes in features on the earth’s surface. My discovery of the blue tarps seen in satellite imagery was an opportunity to answer the question of how to track recovery in a systematic fashion for months to years after an event.

Figure 2. PlanetScope image scene of 3-meter resolution acquired over a neighborhood in North Lake Charles on November 30, 2020 (two months after Hurricane Laura and one month after Hurricane Delta).

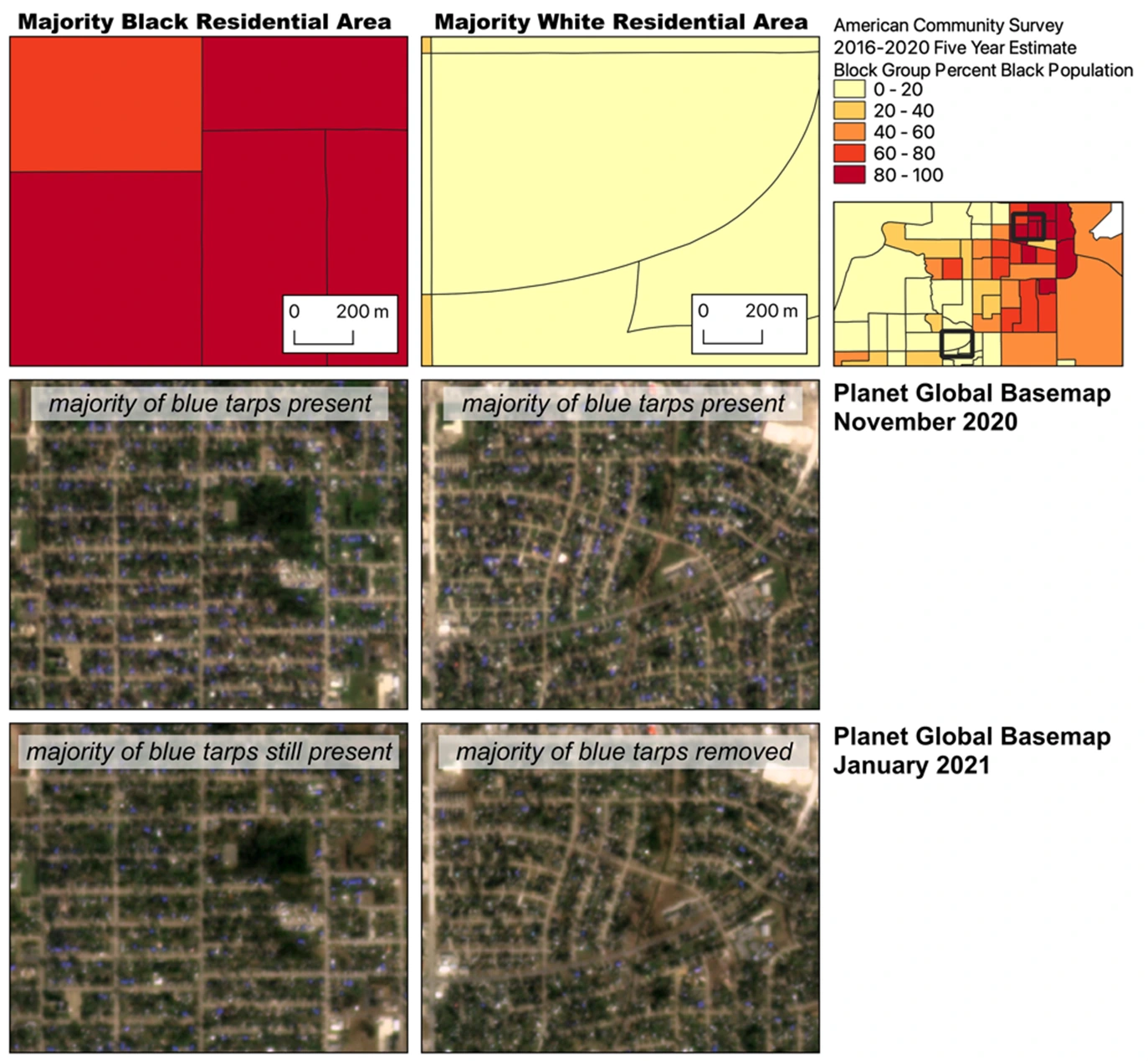

Being from the Midwest with little experience in preparing for and recovering from hurricanes, I spoke with a researcher who studied disaster recovery on the Gulf Coast about my idea of using satellite imagery to map tarps and track recovery. They brought to my attention that while the road ahead for those affected by Ida was long, Hurricanes Laura and Delta, which hit southwestern Louisiana just a year prior in fall 2020, was a series of back-to-back storms that was even further buried in public and national attention. Due to a myriad of reasons, the response to Laura and Delta was severely lacking, owing to prolonged recovery. Imagery from Lake Charles a year after the event still indicated a number of tarps remained on homes. Not only was the duration of tarps remaining on homes startling, but the uneven timing of where and when tarps had been removed showed patterns of disparate recovery rates between majority white and Black neighborhoods in Lake Charles (Figure 3). The different rates of blue tarps being removed indicated that while recovery was delayed for everyone, the delays were more pronounced for communities of color.

Figure 3. PlanetScope imagery shows that tarps remain on longer for majority Black residential areas compared to majority white residential areas.

While satellite maps reveal patterns of recovery as proxied by blue tarps, they do not capture the everyday challenges and decisions individuals and households experience in recovery. I thought back to accounts of wildfire and heat impacted people in Oregon and wondered what stories existed in Lake Charles - stories that needed to be heard and shared. This has led me to develop a dissertation project that marries the maps of tarps with individuals’ experiences of recovery to contextualize patterns revealed in each approach. I’ll be spending the next academic year living in Lake Charles, interviewing residents about what recovery means to them and, in particular, the role that insurance has played in aiding and hindering the recovery process. By using maps and stories to hold the spotlight on places and people that are overlooked, my aim is accumulate evidence of where recovery is inequitable to prioritize areas for rebuilding. In the face of narrow attention and support from past and coming storms, I aspire to have my research advocate for more just recovery and adaptation to future hurricane impacts along the Gulf Coast and beyond.