Managing Changing Landscapes – We Have the Tools to Respond!

Author: Marcos Robles

A slew of articles in the scientific literature and popular media report how the Southwest is one of the epicenters for climate change impacts in North America. Over the last half century, warming across the region has contributed to larger wildfires, widespread piñon tree mortality, declining snow packs and earlier stream flows. While these reports express the urgency of responding to climate change, they also raise many questions.

If you are a natural resource manager or a conservationist, you may ask:

- How have temperatures changed across the habitats you manage, and how does that compare to other habitats?

- Which ecological changes can be tied to warming and climate change?

- What can you and your partners do to respond to such changes?

As part of the Southwest Climate Change Initiative (SWCCI), The Nature Conservancy and partners have completed a report for the Four Corner states of the Southwest that provides some answers to these questions. The report contains the results of a regional assessment of climate change impacts on natural resources. It also highlights lessons learned from four pilot landscapes where natural resource managers, scientists and conservationists are testing different strategies to adapt to climate change. Through SWCCI, we have developed some pretty simple insights that we share below.

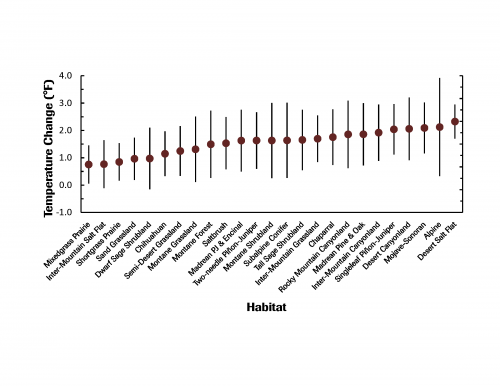

Figure 1:Temperature change across Southwestern habitats from 1951-2006. Note variability across and within habitats.

Wildfire and drought – A different flavor of what we already manage

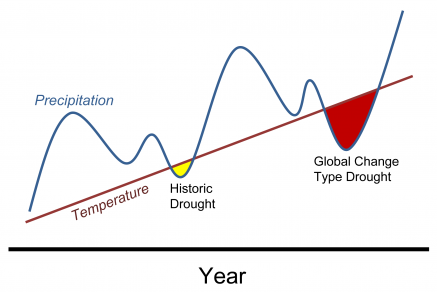

Many of the observed impacts of natural resources are not entirely new phenomena. By increasing evaporative loss of water, warmer temperatures can amplify the severity of natural events that occur when precipitation is scarce, most notably wildfires and drought. While we still have a lot to learn about the interaction of rising temperatures and changing precipitation, a key observation is that we already have tools to manage for drought and wildfires in a variable climate. Why not adjust their use to manage resources in a changing climate?

For example, participants at our Arizona site explored the possibility of adjusting forest thinning and burning treatments to promote snowpack retention and water infiltration as a way to moderate the effects of drought and reduce the risk of catastrophic wildfires.

Figure 2: Warmer temperatures in recent years increase evaporative loss and magnify the water stress experienced by natural systems during drought events. This is conceptual diagram of a “global change type drought,” first described by David Breshears of the University of Arizona.

Monitoring for change

We already have a 50-year experiment in warming in the Southwest and rich and long-term monitoring datasets – but attempts to tie the two together have been few and far between. Can we mine data from historic monitoring datasets, searching for ecological trends that correlate with climate trends? Moving forward, can we adjust our monitoring protocols so that we could capture these relationships?

Luckily, we are not alone. The U.S. Phenology Network and Arizona’s Drought Watch have already been established to share monitoring information about climate change impacts on phenology and drought, respectively.

Local and regional collaboration – a good place to start

We found that evaluating climate change from different scales is a good way to address the challenge. At the landscape scale, partnerships established to address conservation challenges can be re-purposed to tackle climate change.

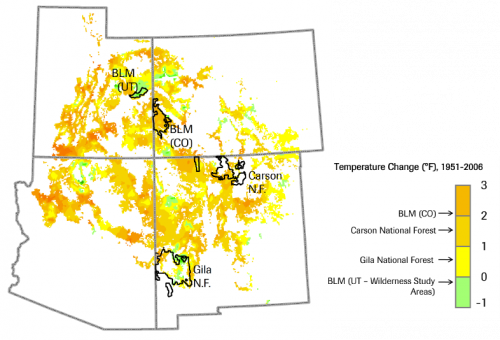

Regional collaboration makes sense because climate and natural resources function across regional scales. Take piñon-juniper woodlands, for example, which occur across the Four Corner states. In the last 50 years, some places where these woodlands occur have warmed 3-4 times faster than other areas. If these patterns persist into the 21st century, meeting objectives to maintain woodlands in these “hotspots” may be challenging. Alternatively, settings where woodlands have remained relatively cool may serve as refugia. At the very least, everyone who manages these woodlands would be well-served to work collaboratively on objectives. Such interchange may ensure that we are maintaining ecological systems in the places where we can while we manage for transitions in those places where we can’t.

Figure 3: Given the uneven nature of warming across two-needle piñon-juniper woodlands, some land stewards are managing woodlands that have warmed considerably more than others. Map shows range of these woodlands across southwest; colors represent temperature change from 1951-2006.

Improving our science, tools, and collaboration

Through SWCCI, we have learned that there is no recipe book for how to respond to climate change. Every response may vary based on local and regional circumstances. But at the same time, adaptation is not rocket science - it does not require a wholesale invention of new science and tools. Rather, our experiences suggest that we will make the most progress in the near term by improving the effectiveness of our current science, tools, and management practices towards meeting the climate change challenge.

SWCCI is a collaborative group established by The Nature Conservancy in 2008 to provide information and tools to natural resource managers and conservation practitioners for climate adaptation in Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado and Utah. Our regional assessment of climate change impacts on natural resources is now available for download.